A human skull believed to be older than a million years could alter our understanding of human evolution.

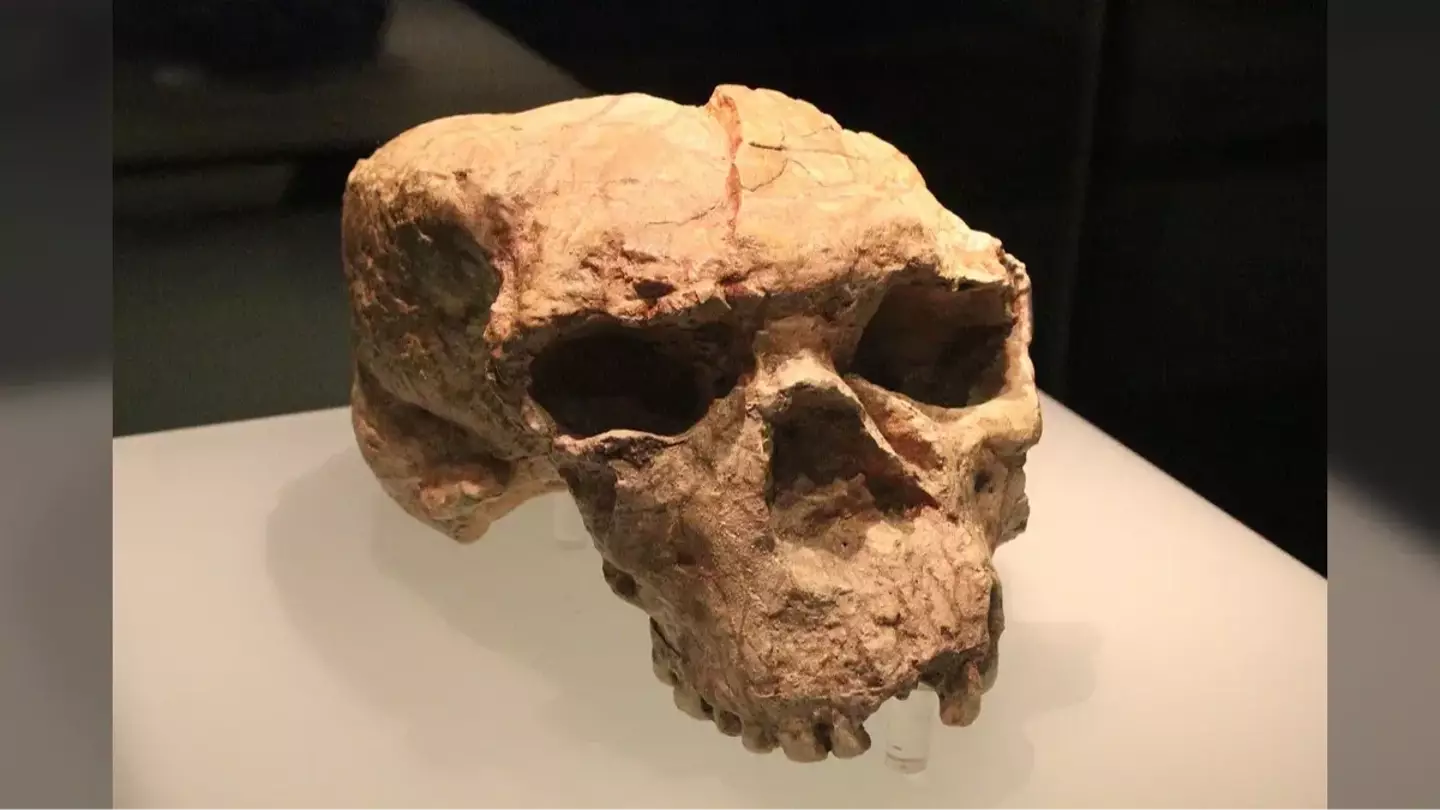

Leading scientists have made a eureka breakthrough after analysing an ancient skull, known as Yunxian 2, discovered in the Yunazian region of China's Hubei province in 1990.

The artefact, found badly deformed and crushed, was previously classified as belonging to a member of the primitive human species Homo erectus, based on its age, large brain case, jutting lower jaw and broad-brush traits.

However, fresh examination poses a new theory, indicating that the overall shape and size of the brain case and teeth make it much closer to Homo longi which, if true, could suggest Homo sapiens first came into existence outside of Africa, the researchers said in a new study published in Science.

Advert

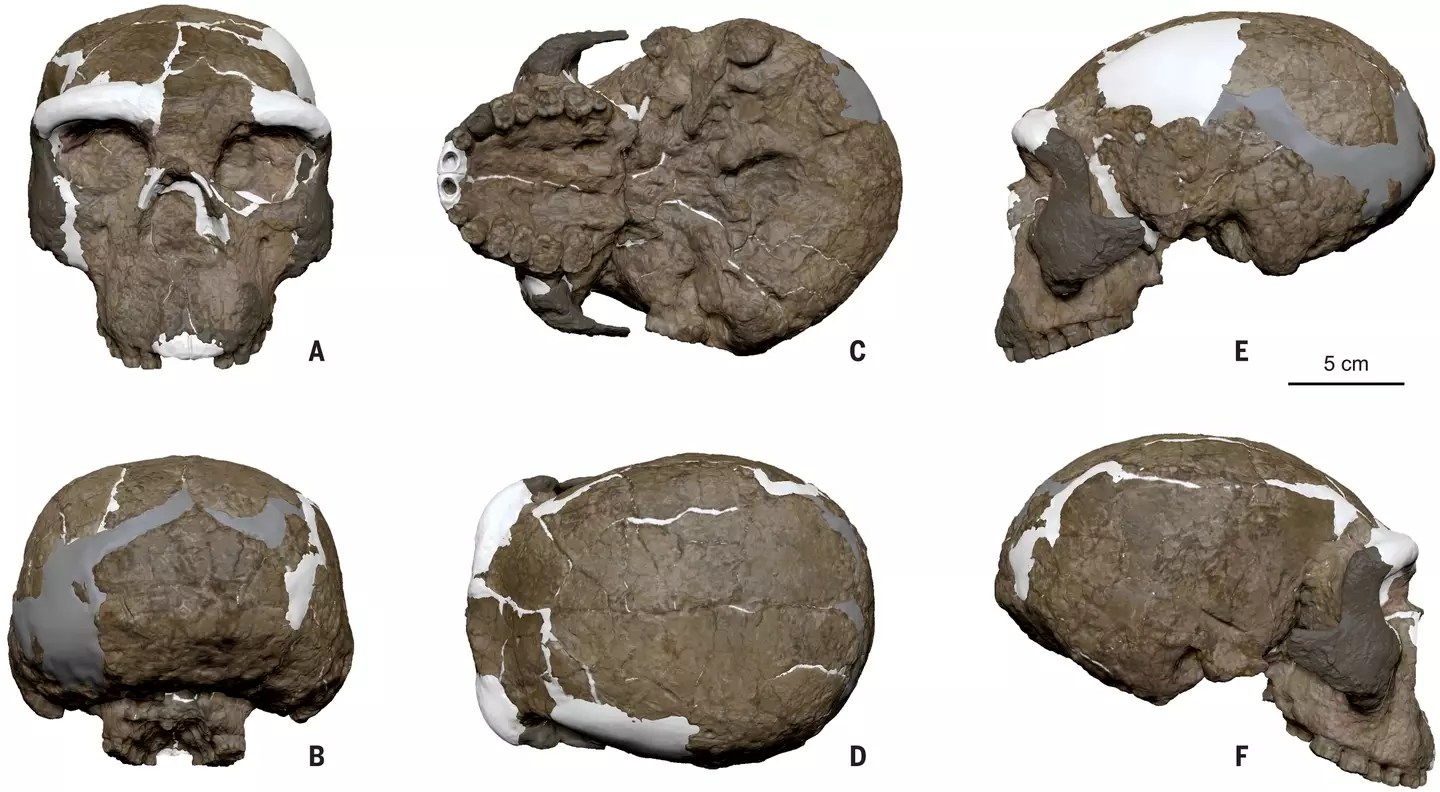

The group applied modern reconstruction techniques to the bone and discovered it could have belonged to this different group, which is more closely linked to Denisovans who lived alongside our ancestors.

The discovery would mark the fossil as the closest on record to split between modern humans and our closest relatives, the Neanderthals and Denisovans, back by at least 400,000 years and present a new understanding of early human's physical traits.

It would also drastically reverse our historic understanding of the last million years of human evolution, posing that the first Homo sapiens possibly originated from Western Asia as opposed to Africa.

Professor Chris Stringer, an anthropologist and research leader in human evolution at the Natural History Museum in London, commented: “This changes a lot of thinking because it suggests that by 1 million years ago our ancestors had already split into distinct groups, pointing to a much earlier and more complex human evolutionary split than previously believed.

"It more or less doubles the time of origin of Homo sapiens.”

He added: "This fossil is the closest we’ve got to the ancestor of all those groups."

The work involved advanced CT imaging and sophisticated digital techniques to reproduce a new virtual reconstruction of the skull.

"We feel that this study is a landmark step towards resolving the ‘muddle in the middle’ that has preoccupied palaeoanthropologists for decades,” the professor continued.

Dr Frido Welker, an associate professor in human evolution at the University of Copenhagen, who was not involved in the research, also weighed in on the matter: “It’s exciting to have a digital reconstruction of this important cranium available," reports The Guardian.

"If confirmed by additional fossils and genetic evidence, the divergence dating would be surprising indeed. Alternatively, molecular data from the specimen itself could provide insights confirming or disproving the authors’ morphological hypothesis.”

Topics: Science, World News, History