If I told you there was $17 million at the bottom of the ocean, how determined would you be to dive in and get it?

Well, the world's most lucrative shipwreck has remained untouched in the Caribbean Sea since it sank some 300 years ago.

And there's a reason why the riches haven't yet been snapped up.

The San José - a 62-gun Spanish galleon laden with treasure - sank on the night of 8 June 1708 after the ship’s powder magazines detonated in a clash with a British squadron off the Barú Peninsula.

Advert

Miraculously, 11 of the 600 sailors on board survived, but the rest tragically perished.

With them went an estimated $17 billion in gold, silver and emeralds, which had been mined in Bolivia and loaded in Portobelo, Panama, on its way to the Spanish treasury.

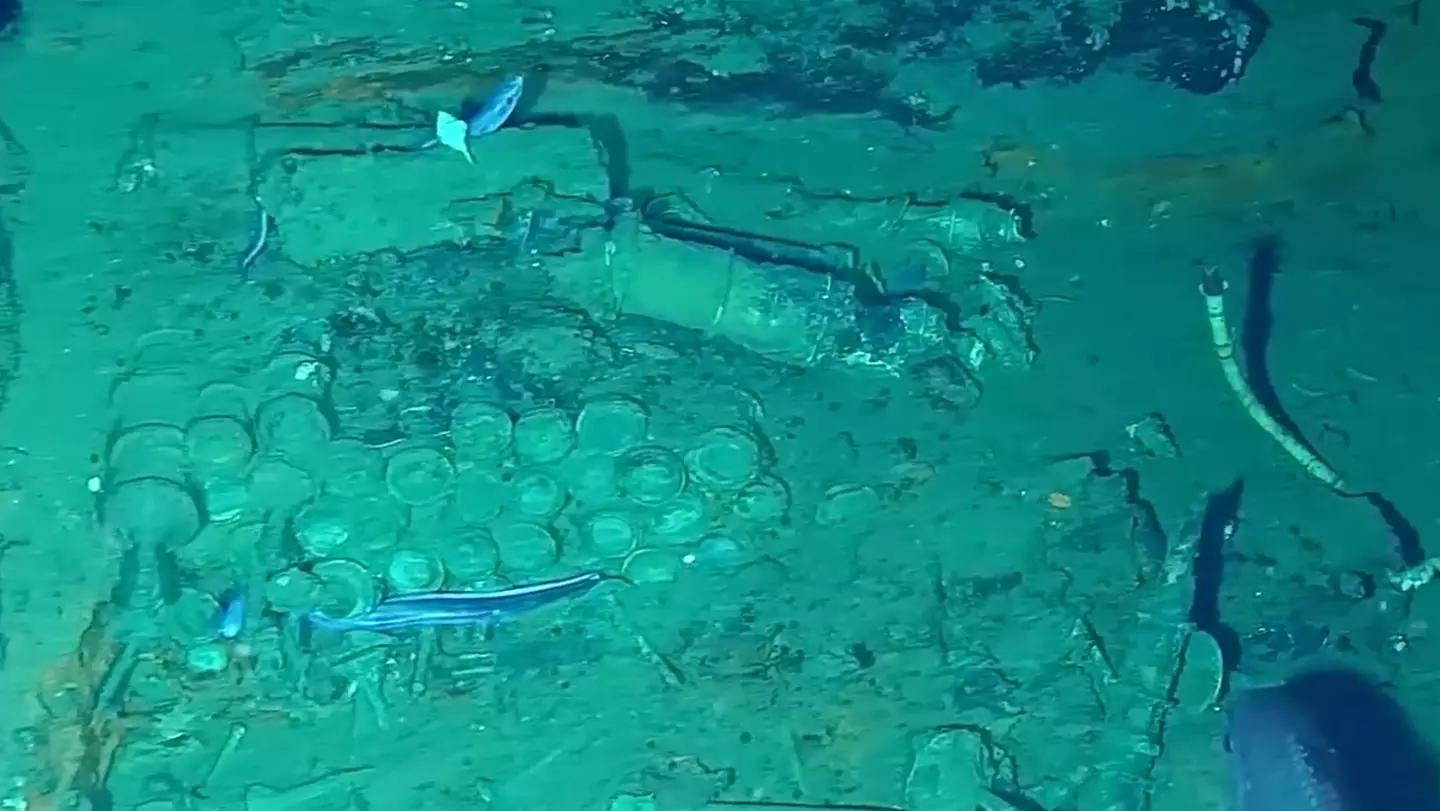

The wreck wasn't picked up until pretty recently, when the Colombian Navy teamed up with scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in 2015. Their deep-diving robot, REMUS 6000, mapped the seabed - just off Cartagena, Colombia - 600 meters down and captured some astonishing evidence.

Their footage showed 62 bronze cannons, Chinese porcelain, and tight clusters of hand-struck 'cob' coins.

Many are stamped with the Jerusalem Cross, confirming the vessel’s identity - as seen in photos published in the journal Antiquity on June 10.

"Coins are crucial artefacts for dating and understanding material culture, particularly in shipwreck contexts," lead researcher Daniela Vargas Ariza said.

"Hand-struck, irregularly shaped coins - known as cobs in English and macuquinas in Spanish - served as the primary currency in the Americas for more than two centuries."

So, a decade on, why haven't these expensive treasures been recovered?

For context, the Titanic lies over six times deeper than San José - albeit 4,286 kilometers (2,663 miles) away, in the treacherous underbelly of the Atlantic Ocean.

While both require specialized equipment to explore, the Titanic’s resting place pushes the limits of technology and (safe) human access, whereas the San José, at 600 meters, is within the typical range for many modern remotely operated vehicles used in marine archaeology.

So, while recovery missions of any kind are dangerous, this one certainly isn't impossible.

Anyway, because the San José lies in Colombian territorial waters, Bogota claims ownership and has outlined a phased robotic recovery plan, launched in 2024, that would eventually display artefacts in a purpose-built maritime museum.

Yet Spain insists the galleon is a protected state war-grave. Meanwhile, US salvage firm Sea Search Armada claims it located the wreck in the 1980s and is pursuing a finder’s fee in The Hague.

Also in the mix are three Indigenous communities - Killakas, Carangas and Chichas - who are pushing for recognition of the forced labour that mined about half the cargo’s metal, pressing UNESCO to brand the hoard 'common and shared heritage'.

So yes, there's a lot going on here - but maybe one day the conflicting countries will come to some sort of agreement; hopefully preserving a priceless chapter of history, while still pocketing a share of the treasure, of course.

Topics: History, World News, Spain