Warning: Discussion of mental health conditions, bereavement and suicide.

"Nobody [should] have to die because they have no one to talk to."

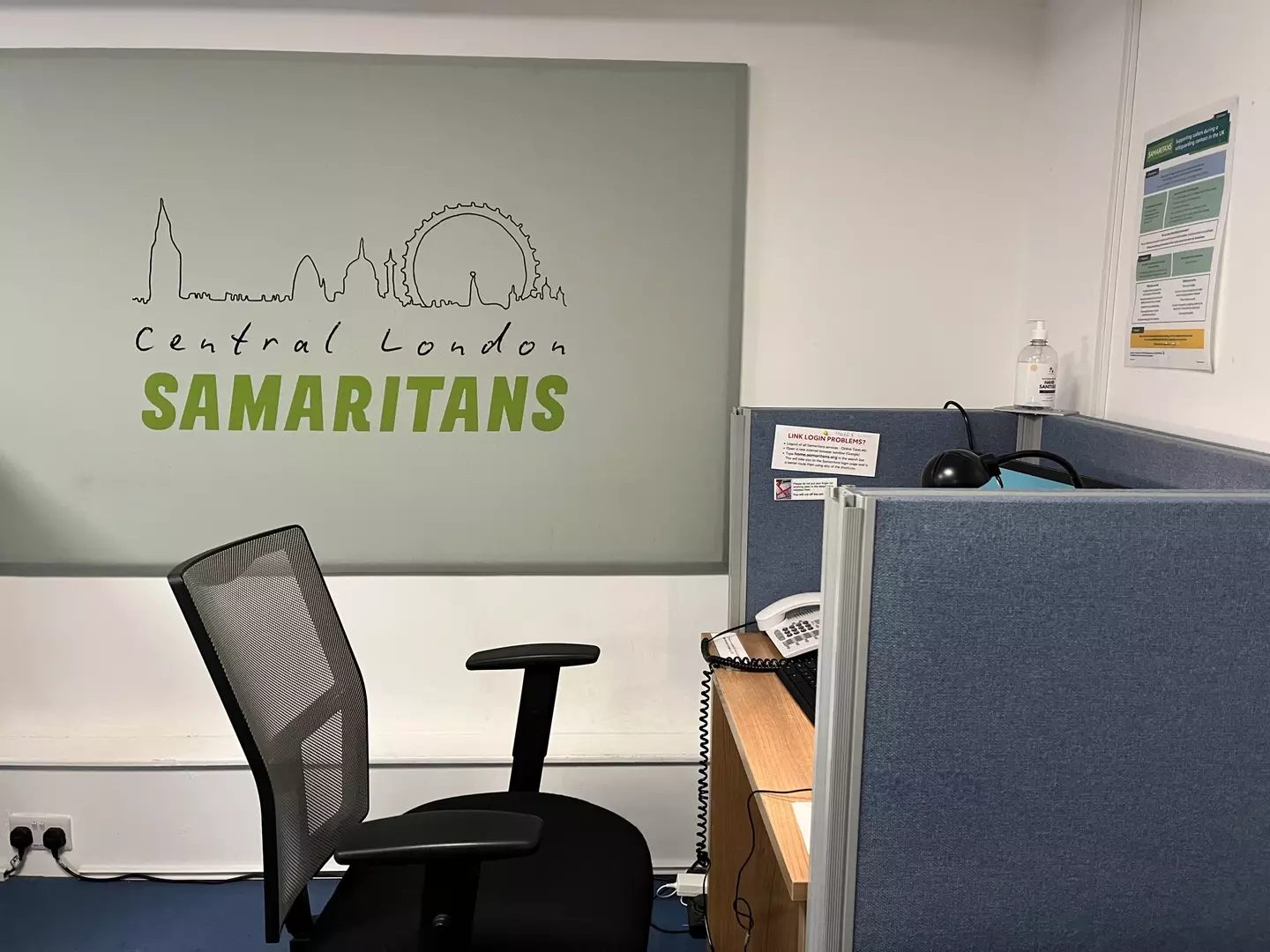

This is a call centre, but not as you know it.

It's an office like countless other, on the surface. Walls covered in colourful posters, a few potted plants, the gentle hum of activity.

Advert

But here, call handers are listening to people speak about how their world has fallen apart after they've lost a relative, or recently self-harmed. Some have called having made the decision to end their own life.

For lots of people, the handlers at the other end of the Samaritans' telephone line are a last resort.

When we talk about mental health, and helplines, we often focus on those who are calling for support. But what about the 22,000 people who are sat behind desks across 201 Samaritans' branches, who volunteer hours of their lives for training, caring and listening, to be on hand 24 hours for those who so desperately want and need to be heard?

"The most challenging thing about being a Samaritan is you don’t know what you’re about to hear," said Mark, a therapist and listening volunteer.

"Before the first shift, I’d had time to think about it. ‘What am I doing? This is going to be a nightmare, I’m going to say all the wrong things and then ruminate about it and take it home and worry'," he reflected.

However, Mark 'found it was completely the opposite' even from shift one.

"Bear in mind shift one is a mentored shift, you have somebody who’s very experienced and it’s a very safe environment. But I walked out of here and I thought, ‘Wow that was just amazing.' My head was clear and my conscious was clear. It was great. I was really surprised. I thought it was going to be really hard but it didn’t feel that way," Mark explained.

British Anglican priest Chad Varah founded the Samaritans in 1953 after a girl in his parish took her own life because she thought she had contracted an STD, but had simply started her period.

The organisation has since shed any religious connotation, opening itself up to anyone who needs to talk. But sitting inside its call room for just five minutes, it’s clear the organisation's volunteers have the patience of saints. They are, however, only human.

"Now, five years into it, you do get hard calls, of course you do," says Mark. "Certain things do get to you. But if ever I’m thinking, ‘Perhaps I should have said this, or not said that,’ I sort of ground myself and think ‘You were here, you were kind, you listened,’ that’s the big thing."

When you agree to be a volunteer at Samaritans, you can't give advice, and there is no judgement. That's the code. "And both of those things can be severely challenged," Mark says.

"So often people will say, ‘What am I going to do? What shall I do?’ And sometimes it’s a binary choice. ‘Shall I leave this guy or not?’ And obviously you can’t say, but what you can do is help people explore the options.

"So they decide but you can really help by opening their eyes to what’s going on and open questions are usually the best. Remember you’ve got one mouth and two ears and do it in that ratio."

He also says listeners can simply say 'I don't know' to people who ask them what to do.

The call handlers have to deal with a different type of problem at times, however.

"You get quite a lot of sexually demanding calls, some of which feel like an abuse of service because people want a voice on the end of the line to tell their fantasies to. So that’s the main abuse," Mark says.

"The training covers it quite well. First thing is you’ve got to give people the benefit of the doubt. If you’re not sure. That can happen quite a lot. So somebody may be legitimately ringing about sexual problems that are having an emotional effect on them and you’ve got to be prepared [for] that.

"When it becomes quite obvious that it’s not what’s happening, then quite often you’d say, ‘I don’t need to know the detail [...] but how is that affecting you emotionally?' Click [put down the call] at that point," he said.

Mark admits these types of calls can result in listeners feeling 'really duped and manipulated'.

As well as those who abuse the service or prank call the helpline for their own misguided sense of fun, there are also some callers who are 'extremely relentlessly angry'.

"It’s not about you but it’s directed at you and sometimes quite personal - they try and get under your skin," says Mark. "I remember I had a guy, we were on for about three quarters of an hour and I must’ve thought 100 times during that call, ‘This guy is really getting to me...it’s not abut you,’ and really reminding myself ‘This guy isn’t doing it for fun. He’s suffering.'

"I could’ve quite legitimately ended it for an abusive call. But right at the end of the call, he said, ‘Well thank you for listening to me. You’ve been more than kind'."

However, most listeners agreed there was one type of call that tends to weigh on their minds the heaviest. And one that, despite all the training, they can never truly prepare for until it happens.

"I think the most difficult kinds of calls are the ones you get when someone actually is attempting to kill themselves as you're on the line," said Deirdre, a listening volunteer and mentor. "You’re talking to people who are very much hanging on by their fingernails."

Mark reflects on one call in which he was able to stay on the line until an ambulance crew arrived to assist the caller - but he says that won't always be the case.

"It usually is the case that you don’t know what has happened to people - and if somebody says, 'Well, actually I think I am going to [end my life], thanks very much but I will...' Those are very difficult calls.

"I think in the end it's about acceptance. You know you’re not going to know. And that’s it. Although we believe suicide is preventable, and we're here to help, people have a right to make their own decisions."

Samaritans become listeners for many reasons. However, another Samaritans worker, Kieran, has reasons that are very personal.

"Often it's because someone we knew, or we were close to, might have taken their own life, or had mental health problems or still does. Again it’s not because we want to fix it - although we’d love to - we just want to help," he said.

"So many Samaritans become Samaritans because we’ve been the lucky ones. And want to try and give something back, as lame as that might sound."

Being a Samaritans listener has also helped some volunteers understand their own mental health better too.

"I’ve been doing this 15 years now. And there are times when - not often but sometimes - a call just trips me up, and I’m not sure why. And you put the phone down and think, 'Why did that affect me so much? You’ve had worse calls than that? Is there something in your own life which chimed with something somebody said?'"

Luckily, another volunteer will spot a listener who has just come off a difficult call, and the Samaritans has a separate volunteer support section branch on hand specifically to help volunteers.

Sarah, 24, who volunteers in the Preston branch, joined Samaritans as a listener after she lost a football teammate to suicide in 2016. "It did take time but it has helped me to be more comfortable talking about it [suicide]," she says.

"I’ve realised that I may be stronger than I thought. I don’t know if it’s courage, or what the word is – but I realise I can probably do more than I thought I could.

"The training, and learning how to listen with empathy, and how to truly, truly be there for someone in their moment of crisis – and how to stay calm and think clearly. That has filtered into my day-to-day life and has really benefitted me," Sarah says.

For Mark, the work allows his to de-stigmatise all sorts of issues simply by listening to those affected talk about them. "It makes you...comfortable - I'm not sure it’s the right word - to talk about suicide very openly.

"The grounding principle is we know that talking about suicide can only ever help. It might not stop someone taking their own life, but it’s never going to make it more likely. So that’s the kind of fail safe. That helps take some of the pressure off.

"You’re either being neutral or you’re being positive."

Anyone can contact Samaritans, free, any time from any phone on 116 123, or you can email [email protected] or visit www.samaritans.org