Topics: Science, World News

Scientists have been left scratching their heads after discovering an oddity surrounding the seafloor.

From what might be the lost city of Atlantis, to ancient ruins that could rewrite everything we know about our history, researchers have found many things out on the bottom of the ocean floor that leave them with more questions than answers.

However, what’s happening at the bottom of the North Sea is more than just a little confusing - it’s downright weird.

Scientists at the University of Manchester have discovered a process of inversion, which they've dubbed 'sinkites', occurring in the North Sea, which they say ‘defy fundamental geological principles’.

Advert

The sand-core mounts are on top of these sinkites, which occur during stratigraphic inversion (when material is dug up and redeposited).

Stratigraphic inversion, or reverse stratigraphy, happens when the younger layers of the seabed sink, and the older ones rise to stack on top of the structure (via ScienceAlert).

This could be due to a tectonic movement, or even a rockslide, and while common, they have never been seen in such amounts - until now.

"This discovery reveals a geological process we haven't seen before on this scale," said lead study author geophysicist Mads Huuse.

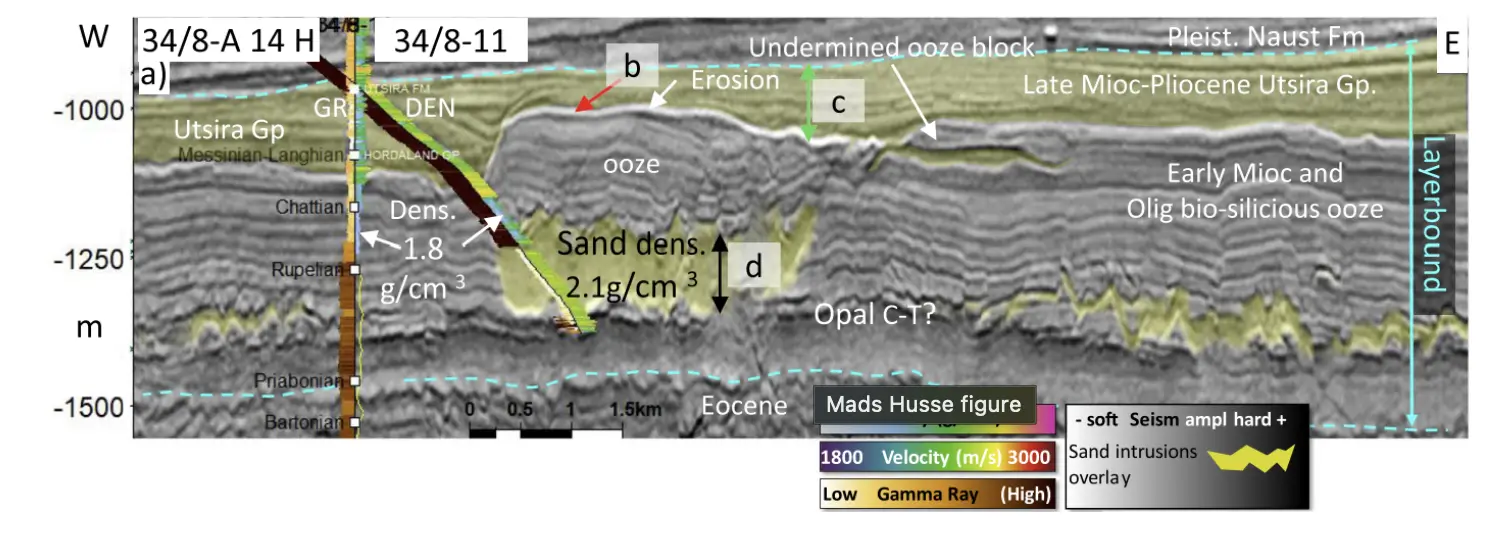

"What we've found are structures where dense sand has sunk into lighter sediments that floated to the top of the sand, effectively flipping the conventional layers we'd expect to see and creating huge mounds beneath the sea."

As expected, the older layers are supposed to go towards the bottom of the formation, and the newer layers follow the order of deposition, according to the study, which was published in Communications Earth & Environment.

The research team believe that the process they found had taken place between the Miocene and the Pliocene era, around 5.3 million years ago.

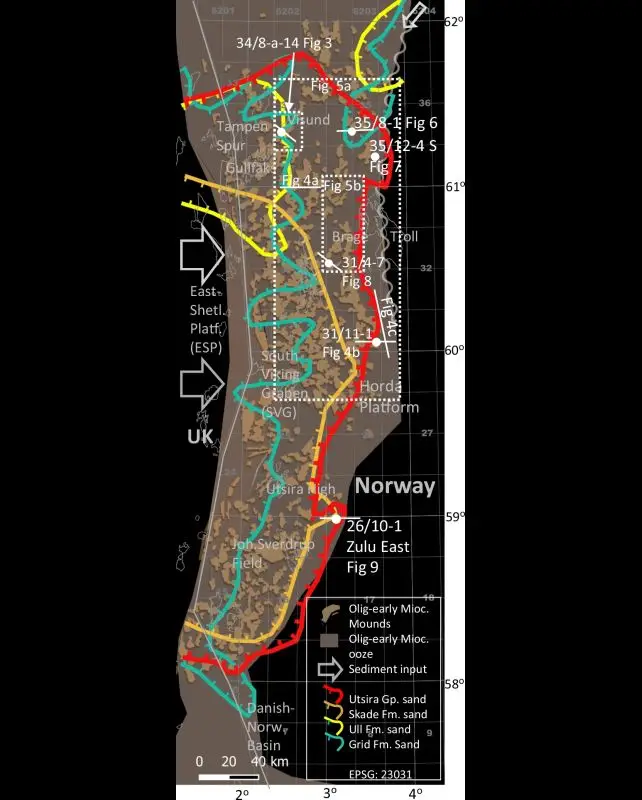

Huuse and geophysicist Jan Erik Rudjord of oil company Aker BP in Norway found the structures in the North Sea using 3-D seismic data.

Acoustic waves propagated through and reflected off the materials, revealing their varying density properties, which led researchers to discover that large portions of the seabed are upside down.

With younger layers of sand buried beneath older layers, they appeared denser and heavier than the softer old layers.

The old layers would be forced upwards, and the younger layers would sink below as the heaviness displaced the layers, essentially flipping them.

Because of this lighter potion on the top, the researchers have dubbed them as 'floatites'.

Currently, researchers are working to understand the ocean floor better and learn more about the process of layer displacement, as it could open up some important information on energy and carbon storage.

"This research shows how fluids and sediments can move around in the Earth's crust in unexpected ways. Understanding how these sinkites formed could significantly change how we assess underground reservoirs, sealing, and fluid migration – all of which are vital for carbon capture and storage," Huuse said.

"As with many scientific discoveries, there are many skeptical voices, but also many who voice their support for the new model.

"Time and yet more research will tell just how widely applicable the model is."