Scientists have discovered they’ve been looking for aliens in all the wrong places, having narrowed down the best types of planets to support ‘complex life’ in a new study.

A team of researchers led by Anna Shapiro of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany found that extraterrestrial life may be more likely on planets with a very specific property – and not necessarily one we’ve focused on before.

They discussed their findings in a new paper titled ‘Metal-rich stars are less suitable for the evolution of life on their planets’, which was published yesterday (18 April) in Nature Communications.

Through their research, they found that planets hosted by stars with low metallicity ‘may be more suitable for life’, having investigated the link between stellar metallicity and UV protection.

Advert

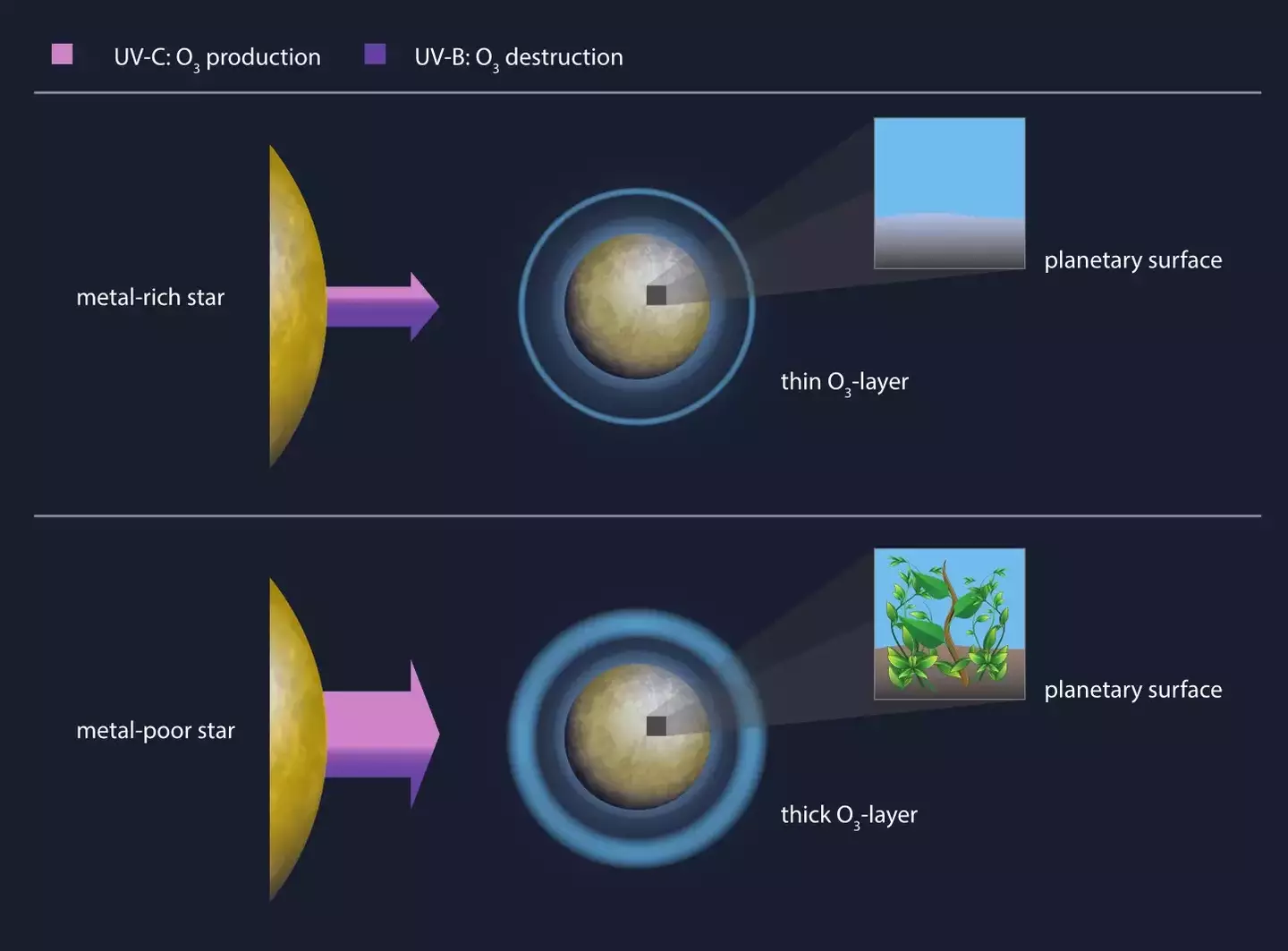

The team explained how, ‘paradoxically’, while metal-rich stars (like the Earth’s Sun) emit ‘substantially less ultraviolet radiation’ than metal-poor stars, the surface of their planets is actually exposed to more intense UV radiation – the exposure of which can lead to genomic damage and is a threat to all life forms.

Previously, scientists have tended to focus on the gas envelopes of planets orbiting distant stars. However, the new study turns the attention to the ozone content of atmospheres surrounding such planets.

The team wrote: “Atmospheric ozone and oxygen protect the terrestrial biosphere against harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Here, we model atmospheres of Earth-like planets hosted by stars with near-solar effective temperatures (5300 to 6300 K) and a broad range of metallicities covering known exoplanet host stars.

“We show that paradoxically, although metal-rich stars emit substantially less ultraviolet radiation than metal-poor stars, the surface of their planets is exposed to more intense ultraviolet radiation.

“For the stellar types considered, metallicity has a larger impact than stellar temperature. During the evolution of the universe, newly formed stars have progressively become more metal-rich, exposing organisms to increasingly intense ultraviolet radiation.”

They added: “Our findings imply that planets hosted by stars with low metallicity are the best targets to search for complex life on land.

It seems counter-intuitive, as stars with lower metal content emit more UV light, but the researchers argue that a planet with an oxygen-rich atmosphere actually has a thicker ozone layer – in turn providing more protection.

Dr. Anna Shapiro, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, said: “We wanted to understand what properties a star must have in order for its planets to form a protective ozone layer.

“We saw huge peaks in intensity. It is therefore quite possible, that the Sun, too, is capable of such spikes in intensity. In that case, also the intensity of the ultraviolet light would increase dramatically.

“So naturally we wondered, what this would mean for life on Earth and what the situation is like in other star systems.”

Topics: World News, Science, Aliens