"I had grown up in an environment where a lot of us as Black people were taught to hate ourselves. To survive we had to make ourselves be the butt of the joke."

In the early 2000s, Gamal Turawa became the first Black Metropolitan police officer to come out as gay. Although he was celebrated at the time, he admits he joked about his skin colour in order to 'survive'.

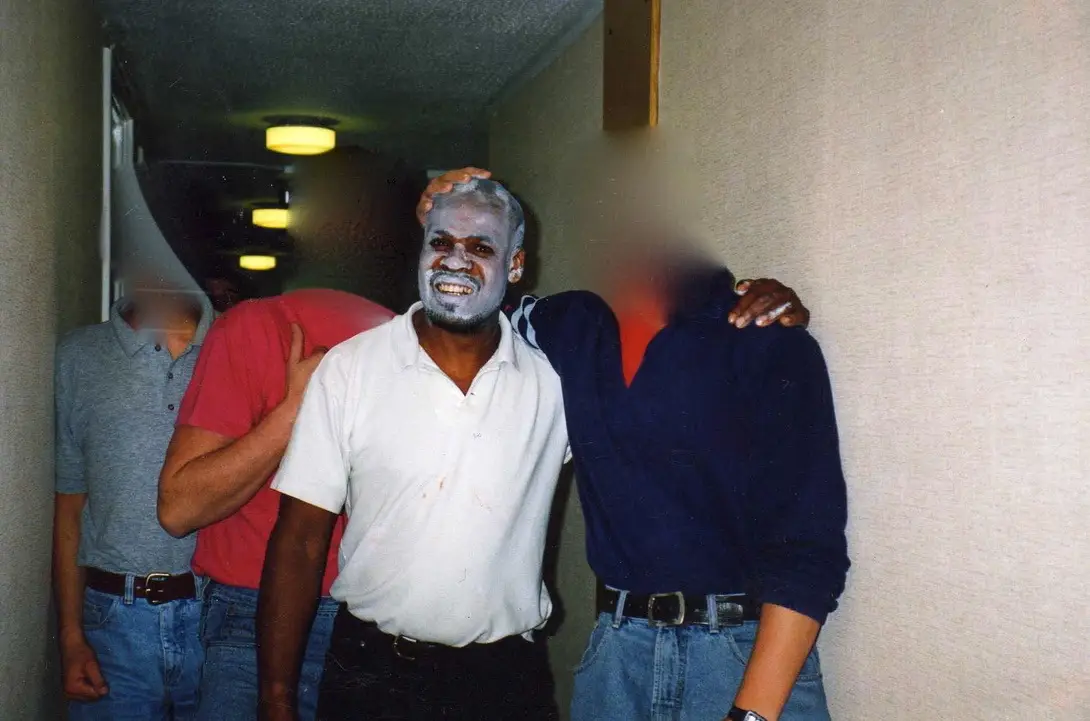

He jokingly referred to his fingers to 'Kit Kats' and on one occasion allowed other members of the force to paint his face white – so he could finally 'fit in'.

At the time it was written off as 'part of the fun... it was part of the way you get accepted'.

Advert

Gamal experienced two 'pivotal' moments with police officers in his childhood. The first saw a white officer scoff at him while giving his white friend a coin. It was symptomatic of how he'd seen the world around him in the 1960s and 70s.

"I grew up in the time when Lenny Henry was on The Black and White Minstrel Show," he said. "Where you would regularly hear about Black kids who were trying to jump into a bath of bleach to try and make their skin white, or try to scrub the blackness off the skin, or take talcum powder and make themselves look white," he said.

Gamal grew up with a white foster family and was 'basically taught that the accepted face of success is to be white'.

His second memorable encounter with the police was entirely different, however, when he witnessed a Black officer directing traffic.

"It was the first Black person I'd seen who stood with confidence," he said. "I remember watching him putting his hand up to stop the traffic and this shiver just went through me, so I think the seed was kind of planted there [but] it wasn’t something I was conscious of until years later," he explained.

Gamal joined the Met in the early 1990s. He was one of four people from a minority background in the police training college.

He appears in the Bafta-winning film The Black Cop, directed by Cherish Oteka, in which he remembers joking with white colleagues about his skin colour.

So why did he allow it?

"Life isn’t so clear and so defined," he says. "This stuff is messy. It’s confusing. It doesn’t follow any logical process," he said.

The image of Gamal with his face painted white is one of the most surprising and affecting parts of his story for director Cherish, who explained they felt 'sad' for Gamal while understanding 'the pressures of being a Black person in a predominantly white industry'.

"There is a huge weight that any person in the minority carries with them," they said. "I feel the sadness for the version of him that existed in his early career."

In spite of what he went through to be seen as an equal to his fellow officers, Gamal received mixed reactions upon joining the force – from members of the public and in the police station.

Some members of the Black community called him 'traitor', 'Judas' or 'coconut' – while others went up to him and shook his hand. Some would look on in awe, while others would 'see [him] and just hate [him]'.

The Met has had a troubled year. Accusations of institutional racism, misogyny and the perceived mishandling of serious cases such as Sarah Everard's have led to boss Cressida Dick standing down. It has work to do to rescue its reputation and restore public trust. But first, it needs to get its house in order.

"I can't speak for every other Black officer [but] I've seen people [allow that kind of behaviour] from a gender perspective, from a race perspective, from a sexuality perspective," Gamal says.

It's clear there are still a myriad issues within the Met. Gamal thinks these issues exist 'because we're human' and that it will take 'honest' and 'courageous' conversations to find a solution – not each party simply trying convince the other their viewpoint is the right one.

"[These issues are] not just in the police," he says. "What the police do is they magnify the problem but you would get racism in all sorts of organisations."

"There are a lot of officers [who] join because they want to do the right thing, but their definition of what is right is different to what society may think is right...

"The saddest thing for me is that you have a lot of good officers out there doing great things, but it’s the [negative] ones [...] that create the attitude," Gamal said.

After having previously been made to feel like he had to joke about who he was, things changed for Gamal when he came out as gay.

The admission was in response to a comment from a colleague about his dating life, and though it wasn't planned Gamal says it came at a point when he had 'run out of lies'.

The more he told people, the more he felt free. In a sad irony he experienced homophobia from his own family, but felt the police was 'probably the safest place' for him to be.

By coming out, Gamal officially became the first openly gay Black officer in the Met.

At the time, he remembers 'loving' the attention. "Who doesn't like a bit of attention every now and again?"

But the pressure of distancing himself from who he was took a toll. He later suffered a breakdown and came close to taking his own life. He hated the world he'd created for himself. The way he'd allowed others to behave and how he'd legitimised it.

"I wasn’t doing that stuff maliciously," Gamal says. "I was doing it from a place of unawareness. Once I understood that, I actually felt sympathy for me as opposed to guilt or shame."

Gamal decided to use his own story to help raise awareness, becoming a diversity trainer in the police.

He officially left the Met in 2018 to focus on telling his story to officers in police forces and other organisations, becoming a 'facilitator for courageous conversations'.

Cherish hopes the film can provide a platform for marginalised communities – as well as make people think about their own behaviour.

"I was keen on shining a light on banter culture and how it is two sides of the same coin with overt racism," they said. "Laughing while saying a racist comment doesn’t stop it from being racist.

"As well as this I want audiences to use this film as an opportunity to meditate on their own self-hate, where it came from and how they can transform it."

As for Gamal, he hopes the release of The Black Cop will 'do the work it needs to do by itself'.

"This isn’t about attacking anyone or blaming anyone," Gamal said. "This is about saying this stuff is messy, we need to have honest conversations about it."

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this article and wish to speak to someone in confidence, contact Stop Hate UK by visiting their website www.stophateuk.org

If you’ve been affected by any of these issues and want to speak to someone in confidence, please don’t suffer alone. Call Samaritans for free on their anonymous 24-hour phone line on 116 123